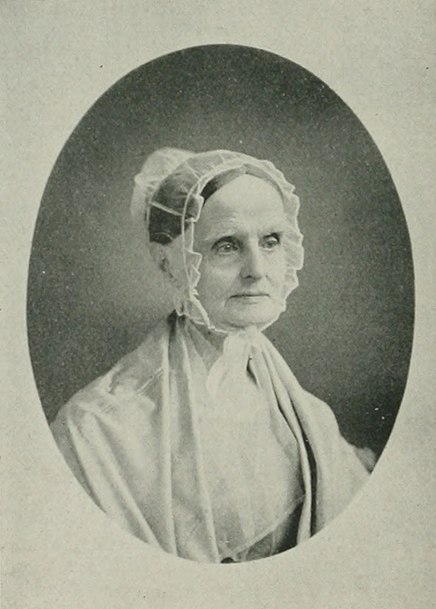

"A charismatic leader, Susan B. Anthony used her organizational ability and her political acumen to help gain suffrage and other rights for women. With her political partner Elizabeth Cady Stanton, she carried the women's rights message across the country, educated women about the legal and constitutional barriers to their full citizenship, and organized the National Woman Suffrage Association.

Born in Adams, Massachusetts, Anthony, a Quaker, attended Deborah Moulson's Seminary for Females when she was 17 years old. After teaching and serving as a headmistress at other schools for several years in her twenties, she left teaching to manage her family's farm in 1849. Her parents had created a gathering place for temperance activists and abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Wendell Phillips. In addition, her parents and younger sister had attended the 1848 women's rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York.

Anthony entered politics through the temperance movement, making her first speech as president of the local Daughters of Temperance in 1849. It was through her temperance work that Anthony met Amelia Bloomer in 1851 and through her, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who had helped organize the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention. At a Sons of Temperance meeting in 1852, Anthony stood up to speak but was told that women were supposed to listen and learn and was denied permission to speak. When she walked out of the meeting, it was her first spontaneous protest action. In response, she organized the Woman's State Temperance Society, with Stanton serving as president.

Anthony attended her first women's rights convention in 1852 in Syracuse, New York, where she became convinced that without the right to vote or to independently own property, women had virtually no political power. She had found the issue to which she devoted the rest of her life—women's rights.

Anthony and Stanton began their cooperative reform efforts in 1854, working to expand married women's legal rights. They sought to secure for married women the rights to own their wages and to have guardianship of their children in cases of divorce. Anthony organized door-to-door campaigns throughout New York, soliciting signatures on petitions for these causes. The Married Women's Property Act, passed in 1860, gave a married woman control over her wages, the right to sue, and the same rights to her husband's estate as he had to hers.

The partnership that developed between Anthony and Stanton resulted in some ways from their personal circumstances and strengths. Stanton, who was married and had children, had little freedom to travel and organize, but she could develop arguments to support women's rights and write speeches and articles. Anthony, who was single, did not have the same responsibilities, and her strengths included organizing and publicity. Through their work, the two women challenged the assumptions that confined women to the private sphere. They argued that gender did not limit a woman's ability to think, that women were not made to serve men, and that women and men should receive the same education in co-educational settings.

In addition to working for women's rights, Anthony was active in the abolitionist movement. By 1856, Anthony was the principal agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society in the state of New York. With the creation of the Republican Party, Anthony began advocating the inclusion of a plank in the party platform for the immediate emancipation of slaves, a proposal that provoked angry responses. Lecture halls she had reserved were denied to her, effigies of her were burned, and violent mobs threatened her. To further the cause of emancipation, Anthony and Stanton founded the Woman's National Loyal League in 1863, advocating the freedom of all slaves and constitutional guarantees for their rights. Under the auspices of the league, Anthony led a national petition drive for emancipation, obtaining 400,000 signatures in support of the cause. After Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1865, the Woman's National Loyal League disbanded.

In 1867, Anthony and Stanton went to Kansas, where referenda on African American and woman suffrage amendments were being held. Republican leaders supported African American suffrage but were silent on woman suffrage, which convinced Anthony and Stanton that the party would not promote the woman suffrage measure. During the campaign, Anthony and Stanton met George Francis Train, an eccentric, wealthy Democrat, whose racist and pro-slavery views were well known. Train campaigned for woman suffrage and against the measure for blacks, often appearing onstage with Anthony. Her alliance with Train created a scandal among Republicans and abolitionists, which ridiculed and discredited Anthony as a woman suffrage leader. Kansas voters defeated both amendments.

A constitutional amendment for woman suffrage was introduced in Congress for the first time in 1868, as was the proposed Fifteenth Amendment, which granted suffrage to male former slaves, but not to women. The next year, Anthony and Stanton organized the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) to develop support for the woman suffrage amendment and opposition to the Fifteenth Amendment as long as it excluded women. In addition to its call for woman suffrage, NWSA advocated divorce reform and working women's rights. In response, two other suffrage leaders, Lucy Stone and her husband Henry Blackwell, organized the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), which supported the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment and advocated working for state woman suffrage amendments. The two groups competed for more than 20 years.

Seeking alternative strategies for voting rights, Anthony and other suffragists began reconsidering the Fourteenth Amendment as a route to the voting booth. Some suffragists believed that the amendment's identification of citizens as male and the Fifteenth Amendment's provision that citizens were voters combined to exclude women from voting.

Other suffragists argued that the Constitution permitted states to define the qualifications for voting. Anthony concluded that she was a citizen and that the Constitution did not specifically prohibit women from voting. She cast her ballot in the 1872 presidential election in New York State. Fifteen other women joined her, and all of them were arrested. Charges were dropped against all but Anthony. Her trial was scheduled for early in 1873, time she used to travel the state of New York, lecturing on the reasons that she believed women could legally vote. Using the Declaration of Independence, the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution, and the Fourteenth Amendment, she argued:

“It was we, the people, not we, the white, male citizens, nor we the male citizens; but we, the whole people who formed this Union. We formed it not to give the blessings of liberty but to secure them; not to the half of ourselves and the half of our posterity, but to the whole people—women as well as men. It is downright mockery to talk to women of their enjoyment of the blessings of liberty while they are denied the only means of securing them provided by the democratic, republican government, the ballot.”

In 1890, Anthony helped with the merger of the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association into the National American Woman Suffrage Association(NAWSA). Stanton served as NAWSA's first president from 1890 to 1892. Anthony was vice-president-at-large those years and succeeded Stanton as president from 1892 until 1900. Anthony made her last public statement in 1906, at a gathering of suffragists celebrating her 86th birthday. After expressing her appreciation to her friends and colleagues and after noting that suffrage had not been won, she said, “with such women consecrating their lives, failure is impossible.” Her declaration, “failure is impossible,” became a motto for suffragists and for feminists who followed later in the 20th century. The Nineteenth Amendment granting women the vote was ratified in 1920, 14 years after Anthony's death."

Source:

Anthony, Susan Brownell (1820-1906). (2013). In S. O'Dea, From suffrage to the Senate: America's political women : an encyclopedia of leaders, causes & issues (3rd ed.). Amenia, NY: Grey House Publishing. Retrieved from https://columbiacollege.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/ghssapw/anthony_susan_brownell_1820_1906/0?institutionId=5445

"Elizabeth Cady Stanton was one of the primary organizers of the 1848

"Elizabeth Cady Stanton was one of the primary organizers of the 1848