“Exhaust the little moment. Soon it dies. And be it gash or gold it will not come Again in this identical guise.”

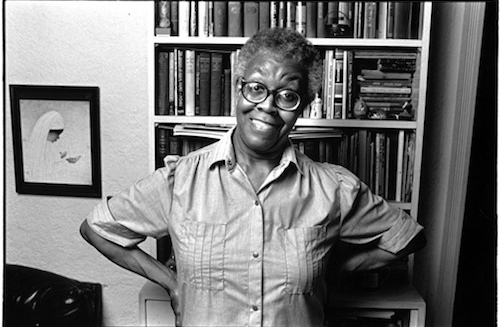

Gwendolyn Elizabeth Brooks was born June 7, 1917, the first child of David and Keziah Wims Brooks. Her birthplace, Topeka, Kansas, was the home of her maternal grandparents, but at the age of five weeks, she and her mother returned to the Brooks’s residence in Chicago, the city in which Brooks would live for most of her life. Her brother Raymond was born in 1918.

David Brooks, a janitor, made only modest wages. His children’s lack of material luxury, however, was offset by a warm home atmosphere that nurtured culture and creativity. David loved to sing, tell stories, and recite poems, while his wife enjoyed singing, playing the piano, and directing plays for young actors.

As a child, Brooks was encouraged to read and to dream. By the time she was seven, she was expressing her thoughts in two-line verses. This precocity prompted her mother to predict that her daughter would one day become “the lady Paul Laurence Dunbar.” Brooks continued to write, producing at least one poem per day, mostly about nature and romantic love. At thirteen, she published her first poem, “Eventide,” in American Childhood. Three years later, she became a weekly contributor to the Chicago Defender’s column “Lights and Shadows.” By the age of twenty, she had published poems in two anthologies.

Much of Brooks’s inspiration came from James Weldon Johnson and Langston Hughes, two well-known African American poets to whom she had submitted several poems for criticism. Johnson concluded that she was indeed talented but needed to acquaint herself with more modern poets such as T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and E. E. Cummings. Hughes also endorsed Brooks’s ability and exhorted her to keep writing — especially about the things she knew.

After graduating from Wilson Junior College, Brooks worked briefly as a maid in a Chicago apartment building and as a secretary to one of its residents, a “spiritual adviser” who sold love potions. The building and its inhabitants would furnish the subject matter for her poem “In the Mecca,” published in 1964.

Frustrated by the inability to find more fulfilling work, Brooks started a mimeographed newspaper that sold for five cents per copy. The paper, News Review, included stories about local events, discussions of cultural issues, brief biographies of successful African Americans, and cartoons drawn by her brother.

In 1939, Brooks married Henry Lowington Blakely II, another aspiring poet. They had two children, Henry in 1940 and Nora in 1951. Henry supported the family through a variety of jobs, while Gwendolyn wrote poems and reviewed books (both novels and collections of poetry) for Negro Digest, The New York Times, and The New York Herald Tribune.

Brooks’s reputation as a poet began with the publication of individual poems in magazines such as The Crisis, Cross-Section, Twice a Year, Common Ground, and Negro Story. In 1945, however, she produced a volume of poems titled A Street in Bronzeville, published by Harper & Row. Four years later, she published Annie Allen, the work for which she won the 1950 Pulitzer Prize for poetry. She was the first black writer to win the award. Brooks also wrote poems for children (Bronzeville Boys and Girls, 1956, and The Tiger Who Wore White Gloves, 1974) as well as several essays, including “Poets Who Are Negroes” (1950) and “They Call It Bronzeville” (1951). In 1953, she published the novel Maud Martha.

Brooks succeeded Carl Sandburg as poet laureate of Illinois in 1968, and in 1985 she was appointed Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. She was named to the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters and received many awards, including the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award, the Shelley Memorial Award, the Anisfield-Wolf Award, the Kuumba Liberation Award, two Guggenheim Fellowships, the Frost Medal from the Poetry Society of America, a National Book Award nomination for In the Mecca(1968), and the National Endowment for the Arts Lifetime Achievement Award in 1989.

Although she was reputed to be shy and introverted, she was eager to share her work and the art of writing poetry. She gave readings at many universities as well as in prisons and taverns. Moreover, she conducted a number of poetry workshops and organized writing contests in elementary and secondary schools, paying the prizes, which ranged from fifty to five hundred dollars, from her own pocket.

Despite her lack of an advanced degree, Brooks taught courses in literature and writing at Chicago’s Columbia College, Northeastern Illinois State College, the University of Wisconsin at Madison, Elmhurst College, City College of New York, and Chicago State University, where she held the Gwendolyn Brooks Chair in Black Literature and Creative Writing. In 1969, however, health problems forced her to resign from teaching, and she devoted herself to the work she most loved: the production of poetry.

Source: Magill’s Survey of American Literature, Revised Edition

Accession Number: 103331MSA10439830000042

And More! Search the catalog to find more books about Gwendolyn Brooks!